Ten years ago I wrote the following about an experience I had at The Met in New York. It’s as honest, true and relevant today as it was then.

May 1, 2015.

Two hours inside the drawing library at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City touched me in a way that I am only now beginning to understand, weeks after the fact.

I went to New York at the invitation of Carrie, my stepdaughter, on a four-day tour organized by her art school. I wanted to learn more and to show my support for Carrie’s decision to study full-time at The Gage Academy of Art. In the end, I came away from the trip with an unexpected lesson in intimacy, a deeper understanding about the human condition.

As soon as The Met opens, I follow Seattle-based artist Mark Kang-O’Higgins, our tour guide, and Carrie through the rotunda. We climb the stairs, then turn left, passing through a gallery of drawings. We arrive at an unmarked door. The dozen or so others in our group gather around.

Behind that door are the librarians charged with storing and caring for The Met’s collection of over one million prints and drawings. This room is not open to the public, though people with research credentials, such as Kang-O’Higgins, can make an appointment in advance and request to view work from the collection.

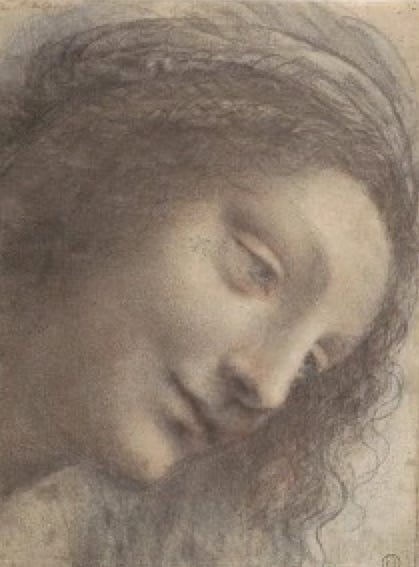

The librarian brings out a da Vinci drawing, “The Head of the Virgin in Three-Quarter View Facing Right,” and all fifteen of us hush. Our faces open to the wonder of the moment. There are no distractions. Bags and mobile phones were left at the door. The only things in our hands are sketch pads and pencils. Tears threaten to spill down my cheeks. It is beautiful and sublime.

A rare feeling comes over me, one that I experience in Catholic churches and in the presence of grand landscapes, such as Yosemite National Park or Tasmania. It’s a feeling that grounds itself in the body. I am suddenly aware of my physicality and that of my surroundings, but a seemingly contradictory temporal fogginess sets in too, a deep sense of connection across time that can’t be described. If I try, I’ll sound like a stoner.

Viewing the da Vinci is an aesthetic experience that connects us with five hundred years of human history, to a genius whose legacy remains relevant today. The heart and mind of Leonardo stands revealed to us. It is a moment of great intimacy.

It doesn’t last long, the collective breath holding. The silence gives way to whispers about the da Vinci and other work that is brought out, including the Degas below. Yet the feeling of intimacy remains.

Art is by its nature intimate. We read a novel and we feel we know something personal and true about the author. So it is for a painting and painter, music and musician, dance and dancer, drama and dramatist, joke and joker.

Seeing the original drawings produced an experience and response that viewing the pictures online could not. Everyone was alive and attentive to the moment, even the librarians snarling, “Don’t touch anything.”

Why? What was so special about this moment that can’t be reproduced by the internet?

I felt comfortable just looking. I didn’t need to look at my phone. I didn’t need to talk. I focussed on what surrounded me, a group of people united by their passion for making and appreciating art. I wasn’t bored for a moment.

Many of us met for the first time the day before; we didn’t have a shared sense of familiarity that might have elevated the moment. Yet, we shared something profound that connected us through space and time, and then poof! The time was up and we were left with our memories.

If we were to regroup now and revisit that moment, the act of reminiscing would in itself be a new experience, as no two remembrances would be the same. If we asked, how was it for you? We would get fifteen different responses. We might find a common thread, perhaps. But everyone would agree that the moment was real. It happened. So, we might ask, then what is reality? What is real for me may not be real for you. Yet, art interprets and abstracts from reality, often with great empathy for the human condition. How can it do this if reality is a function of individuality?

I think that the key to unlocking empathy is not so much imagining myself in the shoes of another, but in understanding that what is real for them is not necessarily real for me; and, therefore, one function of art is to express and represent conflicting, divergent, and common realities. One kind of knowledge lodged within art resides within the intersection between realities expressed by both its creator and the audience who views it, responds to it, attempts to interpret it.

Across cultures there appears a universal need to express ourselves, to represent humanity with all of its contradictions, its goodness and evil, its beauty and its grotesqueness, through artistic representation. Art reveals to us what we think, who and what we are, and also what we wish to be, even when we can’t face these truths directly through discourse. It links the individual to the social. Things fall apart when we’re alienated from each other in both our individual realities and in our art.

What I witnessed in the drawing library can’t be replicated by Facebook, either. Digital social media is about solidifying masks, whereas in The Met that day the masks fell away, as individuals reveled in delight and awe.

In the age of the internet, the physical experience shared in physical proximity with others remains more gratifying than the virtual one. We willingly spend money on airfare and hotel to commune with the thing itself even though we can view it on our phones anytime, anywhere. This need and desire for presence, the stimulation of all our senses, is our way of linking with the real such that we can build a narrative of who we really are for an audience of one, ourselves.

The online world of bits and bytes diminishes us to some extent, though exactly how it does this isn’t something that I fully understand. Perhaps it has something to do with the concept of Facebook envy identified in a study by Ethan Koss at The University of Michigan. Social media makes us feel alienated from others by filtering reality. It creates the conditions that prevent intimacy — jealousy, fear, envy, self-doubt, anger and outrage.

Our online profiles aren’t us, and we know it. Not to know it would mean that we are unhinged, our door to the world fallen from its frame and the boundaries between self and image breached.

I look at LinkedIn and it makes me sad sometimes. All of us clinging to some image of a salable self based on advice from other people on LinkedIn. Few are authentic. Most are guessing at what to share in order to become relevant to an indifferent marketplace.

Online social media is based on excess, on over-production of everything and, in the words of Susan Sontag, the “result is a steady loss of sharpness in our sensory experience.” This explosion in the accessibility of everything, both beautiful and profane, dulls us. We need to see and experience our lives in the dimension of the real, where all of our senses are engaged. Our wellbeing appears to require it.

When we experience with all of our senses we become connected to the social in a way that virtual experiences mitigated by our devices and public personas cannot. Our minds remain profoundly anchored by the physical, and we are diminished by the virtual.

Art affirms that we are exceptional creatures in the known universe. The human brain is the most complex system known to us. So why are we so quick to take reductionist views of human nature and humanity in general, particularly in the age of a digital world where all who wish to connect can? I’m thinking here of Richard Dawkins and his selfish gene, and all the other neo-Darwinists who reduce human nature to a matter of survival of the species and procreation. If this were the case, then why bother with art at all?

Art has no survival benefits that I can name. I suppose we could argue, for example, that it’s a cool way to get chicks into bed, or that beautiful people become actors in order to meet and mate with other beautiful people, but then how would you explain the wretched, solitary writer who wrote a script for them? Or the audience who could have invested the price of the ticket into oysters or Viagra instead?

Art seeks to describe or show that which cannot be portrayed with words alone, only felt. It attempts to reach that part of the brain containing inherited experience and is understood only as feeling and instinct, Jung’s collective unconscious if you like. Science seems to back Jung up on this now, too. Check out this bit of research describing how our genes are impacted by the experiences of our ancestors: Grandma's Experiences Leave Epigenetic Mark on Your Genes

So, if art doesn’t benefit us materially1 then surely we can accept that humans are complicated creatures who have a need for spiritual connection that has traditionally found expression in religious practice, which, historically speaking, spawned a great deal of artistic endeavor.

It’s interesting to note that in an age of religious doubt, doubters like me are reduced to using the language of religion to describe lived experience. Miraculous: the fact of our very existence in the cosmos. Faith: in the ability of science to describe phenomenon we cannot perceive directly with our senses such as atoms, neurotransmitters, and the vacuum of space for example.

And what about the soul? We talk about it all time. People speak of soul mates and soul destroying jobs. But, as Marilynne Robinson points out in her essay, “Freedom of Thought,” both science and the church dumb down the narrative of the soul through reductivism and fundamentalism.

We remain a mystery, a complex one at that. The scientific literature that crosses my desk confirms this day after day, expanding my sense of the miraculous nature of our existence, our planet, our minds.

Art feeds the soul. Science expands knowledge. However, taken in isolation, neither gives us wisdom. We develop wisdom through lived experience and the unexplained miracle of our brains that gifts us with thought, reason, wonder, the ability to pay attention to more than survival and to ask: What does it mean to live well and to be good? Why are we here?

In the drawing library at The Met, the answer became clear to me. Human beings are individuals here for the purpose of connection with each other. Everything we do either brings us closer or pushes us apart. We feel good when we’re connected and lousy when we aren’t. That’s it. This aspect of human nature drives everything else.

Which isn’t true, by the way. Arts and culture industries contribute $7B to the US economy annually. Carrie isn’t a fool to attempt to join such an industry in her own way and in her own time.

Yes, there is power in intimate connections with art, even art made by unknown or little-known artists. Thank you for sharing your experience. The way you described your first connection with art in the Met's prints and drawings room reminded me of moments unpacking art when I was a museum registrar, as well as waiting in anticipation in for a folder in the archives. I'd describe all these experiences as magical!

Loved this essay, Martina. I especially agree with your feelings on the value of art, that we still want to pay to experience the thing itself--not just the digital artifact on the web.